Reviewing if the promises made by Brexiteers have been kept is driving Leaver regret, and acts as a warning to Scottish Remainers.

In the very first article I published on this blog, we looked at “Promising the impossible” – a technique used by Nationalist, Populist Demagogues to signal values to their target voters even when they have no ability or intention to deliver on those promises.

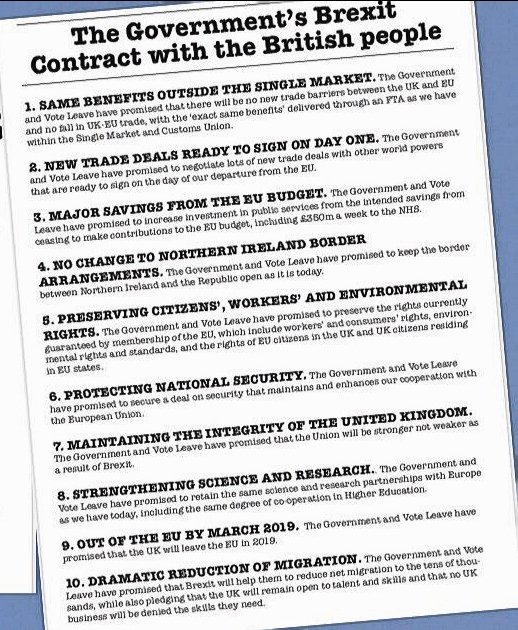

In the course of that, we came across this “Government Contract” by Open Britain outlining the key promises Brexiteers made to voters before the Brexit referendum and continued to make during negotiations. With the Seventh anniversary of the vote having recently passed – and with Scottish nationalist populists still banging their drum but lowering the bar, it seems reasonable to revisit these promises and see which, if any, were kept.

Promise 1: Having the same benefits outside the single market

“What we have come up with … is the idea of a comprehensive free trade agreement and a comprehensive customs agreement that will deliver the exact same benefits as we have.”

David Davis

The promise of having the same benefits outside the single market was a pivotal claim made by Brexit campaigners. David Davis answered a question from Conservative MP Anna Soubry in the Commons in January.

Davis, then the Brexit Secretary, stated in a speech in 2017 that the UK could enjoy a trade relationship with the EU that was

“as frictionless as possible”

while also gaining the freedom to establish trade agreements with countries outside the EU.

However, the reality has been quite different. The UK’s exit from the single market has increased trade barriers, including customs checks and additional paperwork. This has resulted in delays and increased business costs, particularly in the food and drink sector. The promised benefits have yet to materialise, and the UK’s trade with the EU has been negatively impacted.

In 2022, the UK began sliding down the ranks as Germany’s export partner. Once standing proudly in third place in 2016, the year of the referendum, the UK has since tumbled to the eighth spot. The figures are stark – German exports to the UK reached a value of 73.8 billion euros (£63.5 billion) last year, marking a significant drop of 14.1% compared to 2016.

The UK’s departure from the EU has had a “significant adverse impact” on British trade, leading to a reduction in overall trade volumes and a dent in trading relationships with the bloc, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s official public spending watchdog. The OBR’s economic and fiscal outlook predicts that Brexit will result in the UK’s trade intensity being 15% lower in the long run than if the UK had remained in the EU. The Brexit effect continues to ripple through the economic landscape.

We do not have the same benefits outside the EU. ‘Cakeism’ was a gross oversimplification, and this promise was a lie.

Traders and travellers face more paperwork for businesses and people travelling to EU countries, such as customs declarations, export health checks, regulatory checks, rules of origin checks and conformity assessments. This all adds friction to trade, retarding it.

Promise 2: New trade deals ready to sign on day one

“After we Vote Leave, we would immediately be able to start negotiating new trade deals with emerging economies and the world’s biggest economies (the US, China and Japan, as well as Canada, Australia, South Korea, New Zealand, and so on), which could enter into force immediately after the UK leaves the EU.”

Vote Leave Press Release 2016

Liam Fox, the then International Trade Secretary, claimed in 2017 that the UK would have up to 40 trade deals ready to sign “the second after midnight” on the day the UK officially left the EU.

Boris Johnson, during negotiations, claimed we had an ‘oven ready’ trade deal.

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10267938/boris-johnson-vote-tory-brexit/

This promise has not been fulfilled. While the UK has rolled over some of the EU’s trade agreements and negotiated new deals with countries like Japan, it has not achieved the number of ready-to-sign deals worth £800 Billion a year that Brexiteers promised. The trade deals that have been signed have even been described as major blunders.

Boris Johnson’s handling of a £10bn trade deal with Australia has been labelled an “embarrassment” for Britain, with the UK Prime Minister accused of haphazardly making a significant concession. The incident reportedly occurred during a chaotic dinner at No 10 in early 2021, where an Australian official hastily put together an agreement over meat import quotas, which Johnson signed before dessert was served.

The deal involved measuring beef imports by the weight of meat cuts rather than the entire cow, effectively allowing Australia to export more meat to the UK. The Australian high commissioner, George Brandis, allegedly scribbled down the agreement, had it quickly converted into a trade document, and returned it to the dinner table for Johnson to sign.

Promise 3: Major savings from the EU budget

“There will be much-needed public spending paid for by the money we send to Brussels. There will be no cuts to the NHS, only more funding.”

Vote Leave Press Release

The promise of major savings from the EU budget was a cornerstone of the Brexit campaign. The infamous claim that the UK sends £350 million a week to the EU, which could instead be used for the NHS, was emblazoned on the side of the Brexit campaign bus. This claim was made by key Brexit campaigners such as Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, who argued that leaving the EU would free up significant funds for domestic use.

However, the reality of the situation has proven to be far more complex. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s official public spending watchdog, has noted that the economic damage from Brexit is likely to be lasting. In its economic and fiscal outlook, the OBR predicted that the UK’s economy will be around 3% smaller in 2025 than expected if the UK had remained in the EU.

Moreover, the UK’s borrowing has significantly increased due to the economic impact of Brexit. The OBR forecasted that the UK is set to borrow a total of £394 billion in 2020, equivalent to 19% of GDP, marking the highest recorded level of borrowing in the UK’s peacetime history (OBR, 2020). This is a far cry from the promised savings from the EU budget.

The promise of increased investment in public services, such as the NHS, has not materialised as expected. While the government has announced various funding measures, these have often been overshadowed by the economic challenges of Brexit. For example, the government’s plan to provide £1 billion over the next four years to create a stronger, more secure Union has been criticised, with some arguing that this funding is insufficient given the economic impact of Brexit.

The promise of major savings from the EU budget has not been fulfilled. The economic impact of Brexit, including increased borrowing and additional costs, has outweighed the supposed savings from leaving the EU.

This is a stark reminder of the gap between political promises and economic realities.

Promise 4: No change to Northern Ireland’s border arrangements

“The unique status Irish citizens are accorded in the UK predates EU membership and will outlast it. There is no reason why the UK’s only land border should be any less open after Brexit than it is today.”

Theresa Villiers, Vote Leave press releases, 14th April 2016

The promise of no change to Northern Ireland’s border arrangements was a key pledge made by the Brexit campaigners. Boris Johnson, in particular, was vocal about this promise, stating that there would be no checks on goods moving between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK (Conservative Party, 2019).

However, the reality of the situation has proven to be far more complex. The Northern Ireland Protocol, part of the Brexit withdrawal agreement, effectively created a customs border in the Irish Sea, separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK. This led to increased checks and paperwork for goods moving between Northern Ireland and Great Britain, disrupting businesses and consumers alike.

In a recent press release titled “A new chapter for the people of Northern Ireland”, the Conservative Party claimed to have removed the border in the Irish Sea and ensured the free flow of trade within the UK (Conservative Party, 2023). However, this statement glosses over the significant challenges and disruptions that have occurred as a result of the Northern Ireland Protocol.

For instance, the Protocol initially treated goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland as if they were crossing an international customs border. This created extra costs and paperwork for businesses, who had to fill out complex customs declarations. It also limited choice for the people of Northern Ireland and undermined the UK internal market.

Furthermore, the Protocol had implications for the supply of medicines to Northern Ireland. Drugs approved for use by the UK’s medicines regulator were not automatically available in Northern Ireland, creating potential health risks for the population.

In conclusion, the promise of no change to Northern Ireland’s border arrangements has not been fulfilled. Despite recent progress claims, the impact of the Northern Ireland Protocol has led to significant changes and disruptions to trade between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Promise 5: Preservation of citizens’, workers’ and environmental rights

The promise to maintain workers’ rights and environmental standards post-Brexit was a key selling point of the Leave campaign. Leading figures such as Boris Johnson assured the public that the government would not compromise on these protections in the pursuit of Brexit.

Fast forward to the post-Brexit era; the reality is a mixed bag. The UK government has repeatedly stated that it has no plans to lower workers’ rights or environmental standards. However, the potential for future divergence remains a concern. The UK’s Trade and Co-operation Agreement with the EU includes ‘level playing field provisions, but these allow for some divergence t.

In the Conservative Party’s 2019 manifesto, they pledged to strike the right balance between the flexibility that the economy needs and the security that employees deserve, introducing new protections for workers while preserving the dynamism and job creation that drive shared prosperity (Conservative Party, 2019). However, the specifics of these new protections remain unclear, and there needs to be more concrete action to back up these promises.

On the environmental front, the Conservative Party has made several commitments. They pledged to introduce extended producer responsibility so that producers pay the full costs of dealing with the waste they produce and ban plastic waste export to non-OECD countries . They also promised to invest in nature, helping to reach the Net Zero target with a £640 million new Nature for Climate fund. While these initiatives are commendable, they do not directly address the potential divergence from EU environmental standards.

In the wake of Brexit, the UK’s Environment Act of 2021 was designed to fill the void left by departing EU environmental protections. However, the Act has been criticised for falling short of its world-leading ambitions, particularly in areas of environmental governance, forest protection, and air quality.

The Act, which covers areas such as air quality, water, biodiversity, and waste reduction, also established the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) to ensure compliance with environmental laws. However, critics argue that the Act’s details do not meet the high standards initially set by the government.

A key concern is the Act’s approach to deforestation. The Act only restricts forest risk commodities produced ‘illegally’ under producer country laws, leaving a gap for ‘legal’ deforestation, which accounts for about one-third of global tropical deforestation. This is particularly concerning given the Brazilian government’s ongoing efforts to weaken forest protection.

The Act’s proposed air pollution targets have also been criticised. The Act proposes a target to reduce levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) to 10 micrograms per cubic metre by 2040. Critics argue this target is not protective enough and should be achieved by 2030, as research from King’s College London and Imperial College London suggested.

The Act’s consultation process has also been criticised for lacking critical information and being of insufficient length. Despite these criticisms, the government extended the consultation period until 27th June 2022.

The Environment Act is a crucial step towards establishing post-Brexit environmental laws; it is seen as falling short of the government’s initial world-leading ambitions. Critics argue that the Act must be more ambitious and comprehensive to protect the UK’s environment and health.

In conclusion, Environmental rights have been lessened, and workers’ rights are a grey area; while the UK government has made assurances about maintaining workers’ rights and environmental standards, the potential for future divergence and the lack of concrete action to back up these promises raises concerns about the fulfilment of this Brexit promise. The now-cancelled ‘bonfire of EU laws’ saw many rights enshrined in UK law through EU law put at risk, such as TUPE, paid annual holiday, the 48-hour working week, part-time and fixed-term worker regulations, and agency worker regulations; these are just some of the key provisions that protect employee and worker rights which are at more risk than before brexit.

Promise 6: Protecting national security

“But I want to be clear to our European friends and allies: we do not see Brexit as ending our relationship with Europe. It is about starting a new one. We want to maintain or even strengthen our co-operation on security and defence.”

David Davis

The pledge to protect national security was a cornerstone of the Brexit campaign. The Brexit proponents, including Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, argued that leaving the EU would give the UK greater control over its security policies and procedures. They claimed that Brexit would allow the UK to strengthen its borders and enhance its ability to combat terrorism and organised crime.

Fast forward to the post-Brexit era, and the reality of the situation is somewhat different. The UK’s exit from the EU has led to its exclusion from certain EU security databases and mechanisms, raising concerns about the impact on the UK’s ability to combat cross-border crime and terrorism. This is a far cry from the enhanced security control promised by the Brexit campaigners.

In a speech at the Conservative Party Conference in 2022, Home Secretary Priti Patel emphasised the need for vigilance in times of conflict and instability, acknowledging the increased threats that such times bring. However, this statement does little to address the specific security challenges due to Brexit.

Moreover, in a press release titled “Growing the economy by protecting security”, the Conservative Party outlined plans for a new Integrated Security Fund and a refreshed Critical Minerals Strategy, among other measures. Yet, these initiatives do not directly address the loss of access to EU security databases and mechanisms nor provide a clear roadmap for how the UK plans to compensate for this loss.

The promise of protecting national security has not been fully realised in the post-Brexit landscape. While the government has made efforts to bolster national security through various initiatives, the loss of access to key EU security resources presents a significant challenge that has yet to be adequately addressed.

Promise 7: Maintaining the integrity of the United Kingdom

“It’s why we will put the preservation of our precious Union at the heart of everything we do. Because it is only by coming together as one great Union of nations and people that we can make the most of the opportunities ahead.”

Theresa May

As a prominent Brexit campaigner and Prime Minister, Boris Johnson repeatedly promised to maintain the integrity of the United Kingdom. This promise was made in the context of concerns about the impact of Brexit on the relationship between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK and the potential for a renewed push for Scottish independence.

However, implementing the Northern Ireland Protocol as part of the Brexit deal has effectively created a customs border in the Irish Sea, separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK. This has been a source of ongoing tension and has been seen by some as a threat to the integrity of the UK.

The Northern Ireland Protocol is a component of the Brexit withdrawal agreement that aims to prevent a hard border on the island of Ireland. It does this by effectively keeping Northern Ireland in the EU’s single market for goods. This means that goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain are subject to EU customs rules and standards, creating a regulatory border down the Irish Sea.

The Protocol has been a contentious issue. Some argue it protects the Good Friday Agreement by avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Others, however, believe it undermines the integrity of the UK by creating a border in the Irish Sea, referring to the regulatory and customs checks on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland. These checks have been a source of tension, with some arguing they create barriers to trade within the UK. The UK government has sought to address these concerns through negotiations with the EU but, as should have been obvious to anyone before the vote, it’s impossible to square the circle. There must be an international border between the UK and the EU. A hard border between Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland breaks the Good Friday Agreement.

Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) has been a vocal critic of Brexit, arguing that it undermines Scotland’s interests and strengthens the case for Scottish independence. Despite the 2014 referendum where Scottish voters rejected independence, Sturgeon has leveraged Brexit to reignite the independence debate.

Sturgeon has consistently argued that Brexit was imposed on Scotland against its will, as the majority of Scottish voters opted to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum. She has used this argument to claim that the UK government is ignoring Scotland’s democratic voice, fuelling the narrative of a democratic deficit and bolstering the case for independence.

Sturgeon has criticised the UK government’s handling of Brexit negotiations and its impact on Scotland’s economy, rights, and international standing. She has argued that an independent Scotland would be better placed to protect its interests and values, particularly its desire to remain closely aligned with the EU.

However, Sturgeon’s approach – still being mooted by her less impressive successors, was a strategic move to weaponise Brexit for political gain. The SNP still seek to use Brexit to keep the threat of Scottish independence alive and to rally support for the SNP’s independence agenda: but done on a false promise that Scotland could somehow undo Brexit and rejoin the EU. This isn’t borne out by any analysis of the criteria and methodology to join.

Promise 8: Strengthening Science and Research

The promise to strengthen science and research was a key part of the Brexit campaign. Boris Johnson and other leading figures argued that leaving the EU would free up additional funds for investment in these areas.

In the Conservative Party’s 2019 manifesto, they pledged to focus their efforts on areas where the UK can generate a commanding lead in the industries of the future – life sciences, clean energy, space, design, computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence. They also committed to making an ‘unprecedented investment in science to strengthen research and build the foundations for the new industries of tomorrow.’

However, the UK’s departure from the EU has led to its exclusion from certain EU research and development programs, such as the Erasmus student exchange program. While the UK government has announced its own schemes to replace these, there are concerns about whether they will be able to match the scale and impact of the EU programs.

The UK government has made some strides towards fulfilling this promise. In a 2021 speech, the Prime Minister announced a £1 billion Ayrton Fund to develop affordable and accessible clean energy and pledged to use increased R&D funding from the government to attract and kickstart private investment. The government also committed to reforming the science funding system to reduce the time wasted by scientists filling in forms and unlocking long-term capital in pension funds to invest in and commercialise scientific discoveries.

Saying that, these initiatives are still in their early stages, and it remains to be seen whether they will be able to fully compensate for the loss of EU funding and collaboration opportunities. Furthermore, the government’s commitment to making the UK a science and research superpower has been called into question by its decision to cut funding for overseas aid, which includes funding for scientific research into global challenges such as climate change and infectious diseases.

Brexit has significantly impacted the UK’s scientific community, with long-term effects on research, collaboration, and funding.

The UK’s departure from the EU has raised concerns about the country’s ability to attract and retain top scientific talent, as well as its access to crucial international research networks and funding mechanisms.

According to a study by the Royal Society, the UK’s scientific output has been declining since the Brexit vote in 2016, with a notable decrease in the number of papers co-authored with EU scientists. The study also found that the UK’s share of EU research funding has dropped significantly, and the country has fallen from first to third place in terms of the number of leading researchers choosing to move there.

The London School of Economics (LSE) has also highlighted the negative impact of Brexit on UK science. They argue that the uncertainty surrounding Brexit has already damaged the UK’s scientific standing and propose a plan to mitigate this damage, which includes maintaining strong ties with European and international scientific communities, ensuring the mobility of researchers, and securing access to international funding.

The Royal Society is actively working to ensure the best outcome for research and innovation following Brexit. They emphasise the importance of keeping highly-skilled scientists in the UK and attracting talent from around the world. They also advocate for continued access to international funding and networks, including association with the EU’s Horizon Europe programme and maintaining regulations that support access to new medicines, technologies, and collaborations.

In conclusion, while Brexit poses significant challenges to the UK’s scientific community, some efforts are underway to mitigate these effects and ensure the country remains a leading player in global scientific research and innovation. While the UK government has made some progress towards fulfilling its promise to strengthen science and research, there are significant challenges ahead, and the impact of Brexit on the UK’s scientific community is still unfolding.

Promise 9: Being out of the EU by March 2019

The promise that the UK would be out of the EU by March 2019 was made by various Brexit campaigners, including Boris Johnson. However, the UK’s departure date from the EU was 31st January 2020, almost a year later than promised. This delay was due to various factors, including difficulties in negotiating the withdrawal agreement and political deadlock in the UK Parliament.

Promise 10: A dramatic reduction of immigration

The promise of a dramatic reduction in immigration was a key part of the Brexit campaign; as were exaggerated threats of potential future immigration. Boris Johnson, in his speeches and comments, has emphasised the UK’s new ability to control its borders and reform the asylum system. He has also spoken about the distinction between legal and illegal migrants and the power to turn people back at sea, and the Tories have still made their abhorrent anti-refugee ‘stop the boats’ claim central to their rhetoric.

The rise in numbers shows “sustained strength” in post-Brexit migration, despite introducing a point-based visa system for European Economic Area nationals. This could be explained by the continued rise in visas issued to non-EU migrants, which reached 1.1 million in the year to June 2022. Indeed, a rise in commonwealth immigration over European immigration shored up support for Brexit in some existing immigrant and immigrant-descended communities.

While the UK has ended freedom of movement with the EU, it is too early to assess the long-term impact on immigration levels. The new points-based immigration system is designed to attract people with the skills the UK needs rather than reducing overall immigration.

While the xenophobic call to reduce immigration may have played well to some sections of the leave-voting electorate, it is incompatible with the promises of economic success or of protecting the NHS, both of which rely on immigration, especially EU immigration.

Leaver’s Regret, Remainer’s Warning

It’s clear that the Brexit saga has been a tumultuous journey for the United Kingdom. The promises of prosperity, sovereignty, and a brighter future, peddled by populist nationalists, have not materialised as many Leave voters had hoped. In fact, the reality has been quite the opposite.

The economic fallout, the strain on the NHS, and the ongoing political instability are stark reminders of the chasm between the promises made and the reality delivered. It’s no wonder that many Leave voters now regret their decision and think Brexit isn’t going well.

This regret, however, should not be seen as a failure on the part of the voters, but rather as a stark warning about the dangers of populist rhetoric and the empty promises it often carries. It’s a lesson that should be heeded by Remain voters in Scotland as they are targeted by an increasingly desperate nationalist movement.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) and Scottish Nationalism, in general, are poised to employ similar tactics. They will promise what people want to hear – whether that’s undoing Brexit, having more money for the NHS, or ‘taking back control’. These promises are designed to win support and get independence over the line. But as we’ve seen with Brexit, the promises made are often far from what will be delivered.

The allure of these promises can be strong, especially when they align with our hopes and desires. But we must remember that promises are only as good as their fulfilment. The Brexit experience has shown us that populist nationalism often fails to deliver on its promises, leaving in its wake regret and disillusionment.

As we move forward, let us not forget the lessons learned from Brexit. Let us scrutinise the promises made by the SNP and other nationalist movements and demand transparency and accountability. Only then can we make informed decisions that will truly benefit our future.

References

General References

Open Britain, Brexit Contract,

Demagogue, B. (2020, July 8th) Promising the Impossible. Populists playbook https://populistsplaybook.com/2020/07/08/promising-the-impossible/

Henly, J. Roberts, D. ( 2018, March 28). 11 Brexit promises the government quietly dropped. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/ng-interactive/2018/mar/28/11-brexit-promises-leavers-quietly-dropped

Conservative Party. (2019). Conservative Party 2019 Manifesto. https://assets-global.website-files.com/5da42e2cae7ebd3f8bde353c/5dda924905da587992a064ba_Conservative%202019%20Manifesto.pdf

Kwartang, K. Conservative Party. (2020, October 3). Our plan for the economy. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2022/our-plan-for-the-economy

Conservative Party. (2021, July 24). Two Years On: Delivering on our Promises. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2021/two-years-on–delivering-on-our-promises

Sunak, R. Office for Budget Responsibility. (2020, November 25). The Spending Review 2020 in Full. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2020/the-spending-review-2020-in-full

The Guardian. (2016, February 28). Brexit effect everyday life. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/feb/28/brexit-effect-everyday-life

TheyWorkForYou. (2021, March 16). Integrated Review. https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2021-03-16b.161.0&s=speaker%3A10999#g173.2

TheyWorkForYou. (2021, May 11). Debate on the Address: 1st day. https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2021-05-11b.7.1&s=speaker%3A10999#g22.3

TheyWorkForYou. (2021, December 1). Prime Minister: Engagements. https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2021-12-01c.908.5&s=speaker%3A10999#g911.5

Freedland, J. (2023, June 23). With even leavers regretting Brexit, there’s one path back to rejoining the EU. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/23/leavers-regret-brexit-rejoining-eu-nigel-farage

Promise 1: Having the same benefits outside the single market

TheyWorkForYou. (2022, May 10). Debate on the Address: 1st day. https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2022-05-10b.7.1&s=speaker%3A10999#g21.0

Davis, D. (2017). Hansard, Debates. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2017-01-24/debates/d423aee6-be36-4935-ad6a-5ca316582a9c/article50

Promise 2: New trade deals ready to sign on day one

Politico. (2023). Brexit had significant adverse impact on UK trade, says public finances watchdog. https://www.politico.eu/article/brexit-had-significant-adverse-impact-on-uk-trade-says-public-finances-watchdog%ef%bf%bc/

The Independent. (2023). Boris Johnson UK embarrassment Australia. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/boris-johnson-uk-embarrassment-australia-b2350567.html

Promise 3: Major savings from the EU budget

Cecil, N. MSN News. (2023). Brexit an economic disaster for trade between UK and Germany, say economists. https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/newslondon/brexit-an-economic-disaster-for-trade-between-uk-and-germany-say-economists/ar-AA1cS4XF

Promise 4: No change to Northern Ireland’s border arrangements

Edgington,T & Kovacevic, T , BBC News. (2021, August 12). Brexit: What is the Northern Ireland Protocol and why are there checks? https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/explainers-53724381

Bol, D. (2021, July 21). Brexit: UK government seeking ‘significant change’ to Northern Ireland Protocol. Herald Scotland. https://www.heraldscotland.com/politics/19458380.brexit-uk-government-seeking-significant-change-northern-ireland-protocol/

Sunak, R (2023). A new chapter for the people of Northern Ireland. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2023/a-new-chapter-for-the-people-of-northern-ireland

Promise 5: Preservation of citizens’, workers’ and environmental rights

Harrison Clark Rickerbys. (2021). New UK Brexit legislation puts employment rights at risk. https://www.hcrlaw.com/blog/new-uk-brexit-legislation-puts-employment-rights-at-risk/

Honeycomb-Foster, M. Politico. (2021, January 28). UK’s post-Brexit worker rights review no longer happening. https://www.politico.eu/article/uks-post-brexit-worker-rights-review-no-longer-happening/

TheyWorkForYou. (2020, January 9). European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill — Third Reading. http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2020-01-09c.650.5#g650.8

Promise 6: Protecting national security

Conservative Party. (2023). Growing the economy by protecting security. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2023/growing-the-economy-by-protecting-security

Promise 7: Maintaining the integrity of the United Kingdom

Smith, J. (2016, June 24). Brexit: Scotland backs Remain as UK votes Leave. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-36599102

Scottish Government. (2018). Scotland’s Place in Europe: People, Jobs and Investment. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-place-europe-people-jobs-investment/

McEwen, N. (2017, December 19). Brexit and Scotland: between two unions. British Politics, 12(4), 386-400. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41293-017-0066-4

UK Parliament. (2020). The Northern Ireland Protocol. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8777/CBP-8777.pdf

Johnson, B. (2021, July 15). The Prime Minister’s Levelling Up speech in Full. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2021/the-prime-minister-s-levelling-up-speech-in-full

Promise 8: Strengthening Science and Research

Nature. (2018). Brexit is damaging UK science, already. Here is a plan to fix it. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06826-y

BBC News. (2016, July 14). Brexit: The impact on science. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-36834045

Galsworthy, M. Davidson, R. RSE Blogs. (2016, October 3). Brexit is damaging UK science, already. Here is a plan to fix it. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/brexit-is-damaging-uk-science-already-here-is-a-plan-to-fix-it/

Royal Society. (2019). Brexit and UK science. https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/brexit-uk-science/

Promise 9: Being out of the EU by March 2019

The Sun. (2019, November 6). Boris Johnson vote Tory Brexit. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10267938/boris-johnson-vote-tory-brexit/

Promise 10: A dramatic reduction of immigration

Stewart, H. Mason, R. The Guardian. (2016, June 16). Nigel Farage defends Ukip ‘breaking point’ poster queue of migrants. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/16/nigel-farage-defends-ukip-breaking-point-poster-queue-of-migrants

Patel, P. Conservative Party. (2022, March 19). Spring Conference 2022: Speech by Priti Patel, Home Secretary. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2022/spring-conference-2022–address-from-home-secretary-priti-patel