The debate surrounding the economic future of an independent Scotland is complex and fraught with uncertainty. Nationalists propose a path that is both difficult and unprecedented, suggesting that Scotland could either use Sterling unofficially or separate its integrated modern economy from mechanisms such as quantitative easing and control of monetary policy.

Critics, such as John Ferry, in the Courier and The Spectator, have voiced concerns about these proposals. They argue that the economic plans put forth by nationalists are not only ambitious but also potentially destabilising.

Some nationalists are promoting a combination of four books as a solution to these economic challenges. These books are “Doughnut Economics” by Kate Raworth, “Mission Economy” by Mariana Mazzucato, “The Deficit Myth” by Stephanie Kelton, and “The Case for a Job Guarantee” by Pavlina R. Tcherneva.

Each of these works presents a different perspective on new economic theories, and supposedly together could form a comprehensive proposal for how an independent Scotland could navigate its economic challenges; but how accepted are their theories, and what downside risk would relying on them carry?

In this article we will delve deeper into the content and proposals of these four books. We will then discuss how these ideas might play out in reality, considering the potential benefits and drawbacks of each approach. This analysis aims to provide a balanced and informed perspective on the economic prospects of an independent Scotland.

“Doughnut Economics” by Kate Raworth

Kate Raworth is a British economist known for her work on ‘Doughnut Economics’, which seeks to visualise a sustainable economy that is both socially just and environmentally safe. She is a Senior Research Associate at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, where she teaches on the Masters in Environmental Change and Management. She is also a Senior Associate at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership.

Raworth has a long history in the field of economics. She was born in the UK and studied Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford University. She later earned a master’s degree in Economics for Development from the London School of Economics. Her professional career includes a decade as Senior Researcher at Oxfam, and four years as a co-author of the United Nations’ annual Human Development Report.

“Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist” is a book that criticises traditional economic theories that are mainly focused on continuous and infinite growth. Raworth argues that these theories, which were established in the 1960s, are outdated and need to be revised to fit the realities of the 21st century.

I’m actually a fan of the doughnut model and theory, and how it can be considered in the context of the limits to growth.

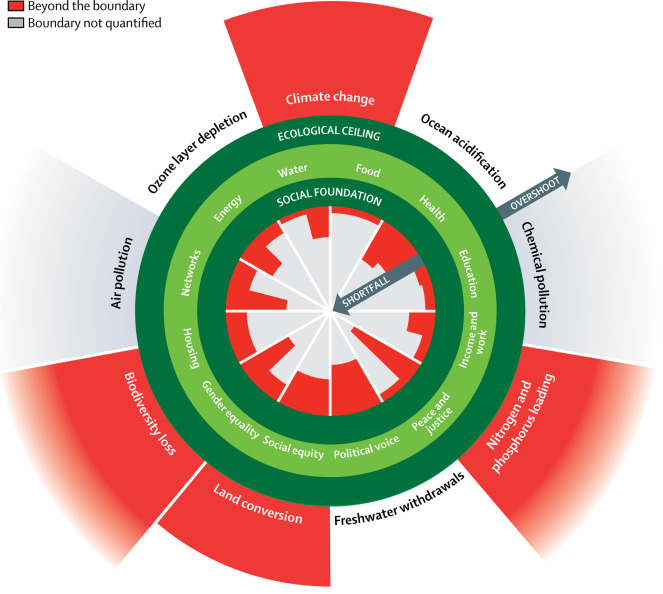

The Doughnut combines two concentric radar charts to depict the two boundaries—social and ecological—that together encompass human wellbeing (figure). The inner boundary is a social foundation, below which lie shortfalls in wellbeing, such as hunger, ill health, illiteracy, and energy poverty. Its twelve dimensions and their illustrative indicators are derived from internationally agreed minimum standards for human wellbeing, as established in 2015 by the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by all member states of the United Nations.

Kate Raworth

The book introduces the concept of ‘Doughnut Economics’, a model that includes twelve aspects of our social foundation, as well as nine planetary boundaries. The ‘doughnut’ refers to the ideal space of our economy, which lies between these two elements. The model is designed to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems. It’s well intentioned, and I found the most credible of the four.

However, while Raworth’s Doughnut Economics has been praised for its innovative approach, it has also faced criticism. One critique is that the model is overly simplistic and does not adequately address the complexities of global economic systems. For instance, Dale (2020) criticises the model for its ‘image-focused’ approach, arguing that it does not sufficiently address issues of class, colonialism, and the growth paradigm.

Another critique is that the model does not provide clear guidelines on how to achieve the balance between social foundation and planetary boundaries. As Ross (2019) points out, while the Doughnut Model makes the missing factors in classic economies visible, it does not provide a clear roadmap for how to transform our capitalist worldview into a more balanced, sustainable perspective.

Ultimately we have 8 billion people and growing on a planet that – with current technology and production – can keep maybe around 1.8 billion people in the doughnut.

“Mission Economy” by Mariana Mazzucato

Mariana Mazzucato is an Italian-American economist who is currently a professor in the Economics of Innovation and Public Value at University College London (UCL), where she is also the founding director of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. Her work focuses on the economics of innovation, the role of the state in the economy, and the economics of growth.

Mazzucato earned her BA in History and International Relations from Tufts University and her MA in International Relations from The New School for Social Research. She also holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the New School for Social Research in New York. She has held academic positions at the University of Denver, London Business School, and the Open University.

In “Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism“, Mazzucato argues for a new approach to capitalism, one that is mission-oriented and aimed at achieving bold and sustainable goals. She draws inspiration from the Apollo moon landing, a mission that required innovation, investment, and the coordination of multiple actors, including the government and various sectors of the economy.

Mazzucato argues that this mission-oriented approach can be applied to solve the pressing challenges of our time, such as climate change and social inequality. She proposes that the state should play an entrepreneurial role, not just fixing market failures but actively creating and shaping markets to achieve desired outcomes.

While Mazzucato’s work has been influential in shaping discussions about the role of the state in the economy, it has also faced criticism. One critique is that her approach may overstate the capacity of the state to effectively direct economic activity. For instance, Pradella (2017) argues that Mazzucato’s work does not sufficiently address the complexities and potential pitfalls of state intervention in the economy.

Her mission-oriented approach may not be applicable or effective in all contexts. Deleidi and Mazzucato (2020) show that mission-oriented policies may produce a larger positive effect on GDP and private investment in R&D than more generic public expenditures. However, the effectiveness of such policies depends on specific institutional and economic conditions that are not present in all countries or sectors.

The fever patriotic focus in a time of prosperity is what took America to the moon; in a post-capitalist age of sovereign individuals and multi-national corporation’s working to starve nations of tax revenue it’s not clear this type of project can be maintained before a collapse in complexity.

“The Deficit Myth” by Stephanie Kelton

Stephanie Kelton is an American economist and academic, who is currently a professor of Economics and Public Policy at Stony Brook University. She is a leading proponent of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a school of thought that challenges conventional wisdom about the role of government spending and debt.

Kelton earned her B.A. from California State University, Sacramento and her Ph.D. in Economics from The New School for Social Research. She has served as Chair of the Department of Economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and as Chief Economist on the U.S. Senate Budget Committee.

In “The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy“, Kelton challenges the conventional understanding of deficits, arguing that they are not inherently bad. Instead, she posits that deficits can be used as a tool to achieve full employment and ensure the provision of public services, as long as they are managed properly.

Kelton argues that the government, as the issuer of its own currency, cannot run out of money and therefore does not need to tax or borrow in order to spend. Instead, the real limits to government spending are resources and inflation. She suggests that policy makers should focus on managing these real limits, rather than worrying about achieving a balanced budget.

While Kelton’s book has been influential in bringing MMT to a wider audience, it has also faced criticism. MMT, also known as ‘magic money tree’ oversimplifies the complexities of economic policy and downplays the risks of deficit spending. For instance, Murphy (2020) argues that having an unfettered printing press is not a magic wand and doesn’t give us more options. It merely gives the Fed greater license to cause boom/bust cycles and redistribute wealth to politically connected insiders.

Another critique is that MMT’s policy prescriptions are not be feasible or desirable in all contexts. Critics argue that while MMT may be applicable to countries like the U.S. that have a high degree of monetary sovereignty, it may not be suitable for countries with less monetary sovereignty or for countries that are part of a monetary union, like also the Eurozone.

Proposing and economy founded on the principles of MMT would make the Scottish economy simply incompatible with the fiscal framework required for EU membership: which is supposedly a key benefit of Scottish independence.

“The Case for a Job Guarantee” by Pavlina R. Tcherneva

Pavlina R. Tcherneva is an American economist, currently serving as an associate professor and chair at the Department of Economics at Bard College. She is also a research associate at the Levy Economics Institute and a senior research scholar at the Center for Full Employment and Price Stability. Her work also primarily focuses on Modern Monetary Theory and public policy.

Tcherneva received her Ph.D. in economics from the University of Missouri-Kansas City and her B.A. in mathematics and economics from Gettysburg College. She has worked with economists from the Levy Economics Institute and the Center for Full Employment and Price Stability on developing a model for implementing a Job Guarantee program in the United States.

In “The Case for a Job Guarantee,” Tcherneva argues for a public policy that provides an employment opportunity to anyone looking for work, regardless of their personal circumstances or the state of the economy. She suggests that such jobs should provide a living wage and decent working conditions, and that a job guarantee should be universal and voluntary – available to all people who wish to make use of it.

Tcherneva argues that a job guarantee makes good economic sense for governments. It would function like a buffer stock programme in agriculture, where the government ‘purchases’ surplus labour at a fixed price. This would address both inflationary and deflationary pressures from fluctuations in employment. She theorises that by providing steady employment, a job guarantee programme would soften the demand on other countercyclical social protection measures, such as unemployment insurance or food assistance.

While Tcherneva’s book makes a compelling case for a job guarantee, it also raises several questions. One critique is that a job guarantee might not be a better proposal than a universal basic income. While a job guarantee programme generates productive assets, reduces the burden of unemployment, and creates a sense of dignity for workers receiving a living wage for an honest day’s work, a universal basic income might perform some of these functions better, especially for those too ill or too old to work.

Another critique is whether a short-term guaranteed job at a living wage is enough to provide the skills to move to employment in the private sector. The private sector is not in the business of hiring people who need jobs, but in making profits. The types of services provided by the private sector reflect this. Today’s gig economy players such as Uber or Deliveroo essentially enable private contracts between individuals, and do not create the kinds of public goods a job guarantee programme might. Will private players now shift to sectors for which the skills acquired in a job guarantee programme will be useful? If not, will the public sector need to continue to provide jobs for workers?

Finally, Tcherneva’s analysis is specific to the United States. It would be interesting to examine the differences between job guarantees in the Global North, where there are well-established social security programmes, and those in the Global South. Tcherneva cites Plan Jefes in Argentina and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) in India as instances of ‘successful’ job guarantees, but does not elaborate on how these are different from the circumstances in the United States, and none of them may be comparable to an independent Scotland.

Government purchase of ‘surplus labour’ but with the ‘dignity of work’ rather than a handout is not a new concept: as shown by the many ‘famine roads‘ in Ireland.

Creative Writing

In conclusion, the economic plans proposed by the Scottish nationalists, when drawing heavily from these four ‘popular counter-economic” books we have examined, present a number of significant challenges and extreme levels of uncertainty. And downside risks.

The idea of using Sterling unofficially or separating Scotland’s economy from mechanisms such as quantitative easing and control of monetary policy is fraught with uncertainty. As John Ferry has argued, such plans are not only ambitious but potentially destabilising. The London School of Economics has also highlighted the economic challenges that an independent Scotland would face, noting that independence could hit the Scottish economy 2 to 3 times harder than Brexit.

The books propose a range of economic theories and policies, most of which are untested and highly controversial. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which is central to Stephanie Kelton’s “The Deficit Myth”, oversimplifies the complexities of economic policy and downplaying the risks of deficit spending (Mankiw, 2020). MMT’s policy prescriptions are not be feasible or desirable in many contexts, especially for countries with less monetary sovereignty (Vergnhanini & Conti, 2018).

Trying to implement the economic policies proposed in these four books simultaneously could lead to conflicts and inconsistencies; Each book presents a different perspective on economic policy, and trying to combine these different approaches could result in a lack of coherence and direction.

It is important for the voters being targeted by such oversimplified messages to know that these books and the economic theories they propose are nowhere near universally accepted. That’s not to say these authors may not be talented or qualified: but all four deviate from accepted norms. There is ongoing debate among economists about the validity and applicability of these theories, and it is unclear how successful they would be in practice. They carry huge downside risk.

The economic plans proposed by the Scottish nationalists are ambitious and innovative, they also present significant risks and challenges.

What is clear is that little work has been done since 2014 to develop a viable economic strategy for an independent Scotland.

There is a structural issue with Scotland’s economy: we spend more than we make. It would take creative writing indeed to turn that into a credible case that independence could even maintain our current public services: never mind increase them.

References:

– Ferry, J. (2023). Scottish independence referendum 2023: Economics. *The Press and Journal https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/opinion/columnists/4680040/scottish-independence-referendum-2023-economics-john-ferry-opinion/

– Mankiw, N. (2020). A Skeptic’s Guide to Modern Monetary Theory. *American Economic Association*. DOI: [10.1257/PANDP.20201102] https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/PANDP.20201102

– London School of Economics (2021). Independence would hit Scottish economy 2 to 3 times harder than Brexit. https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2021/a-Jan-21/Independence-would-hit-Scottish-economy-2-to-3-times-harder-than-Brexit

– Vergnhanini, R., & Conti, B. (2018). Modern Monetary Theory: a criticism from the periphery. *Brazilian Keynesian Review*. DOI: [10.33834/BKR.V3I2.115] https://dx.doi.org/10.33834/BKR.V3I2.115

– London School of Economics (2021). Independence would hit Scottish economy 2 to 3 times harder than Brexit. https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2021/a-Jan-21/Independence-would-hit-Scottish-economy-2-to-3-times-harder-than-Brexit

– Mankiw, N. (2020). A Skeptic’s Guide to Modern Monetary Theory. *American Economic Association*. DOI: [10.1257/PANDP.20201102] https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/PANDP.20201102

– Deleidi, M., & Mazzucato, M. (2020). Directed innovation policies and the supermultiplier: An empirical assessment of mission-oriented policies in the US economy. *Research Policy*. [DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2020.104151] https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104151

– Pradella, L. (2017). The Entrepreneurial State by Mariana Mazzucato: A critical engagement. *Capital & Class*. [DOI: 10.1177/1024529416678084] https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1024529416678084

– Murphy, R. (2020). Book Review: “The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy”. *Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics*. [DOI: 10.35297/QJAE.010069] https://dx.doi.org/10.35297/QJAE.010069

– Ábel, I. (2020). A gazdaságpolitika újragondolása és a válság: Stephanie Kelton: The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. *Közgazdasági Szemle*. [DOI: 10.47630/KULG.2020.64.9-10.90] https://dx.doi.org/10.47630/KULG.2020.64.9-10.90

– Kumar, A. (2020). Book Review: The Case for a Job Guarantee by Pavlina R. Tcherneva. *LSE Review of Books*. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2020/06/29/book-review-the-case-for-a-job-guarantee-by-pavlina-r-tcherneva/

– Raworth, K. (2017). A Doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st century. *The Lancet Planetary Health*. [DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30028-1] https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30028-1

– Spash, C. L. (2020). ‘The Doughnut Economics of Kate Raworth’. *Real-World Economics Review* http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue95/Spash95.pdf